Rizzoli Celebrates African American Artists

February 14, 2020

In honor of Black History Month, we’re celebrating art by African American artists who have made a major impact on the art movements of their day—as well as the art world as a whole—and whom we’ve had the honor to publish.

Image above: LeRoy Clarke, Now, 1970

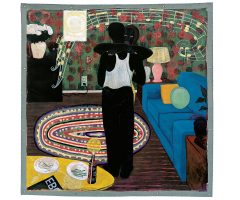

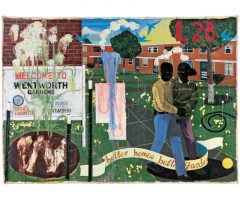

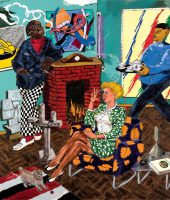

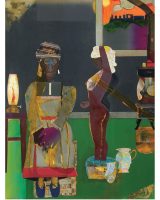

Kerry James Marshall

Kerry James Marshall is one of America’s greatest living painters. Born before the passage of the Civil Rights Act, in Birmingham, Alabama, and witness to the Watts riots in 1965, Marshall has long been an inspired and imaginative chronicler of the African American experience. Marshall explores narratives of African American history from slave ships to the present. His direct and intimate scenes of black middle-class life conjure a wide range of emotions, resulting in powerful paintings that confront the position of African Americans throughout American history.

(from left to right): Untitled, 2009; Slow Dance, 1992–93; Better Homes, Better Gardens, 1994; When Frustration Threatens Desire, 1990; A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980.

From the book Kerry James Marshall: Mastry.

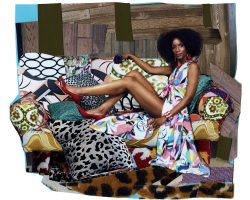

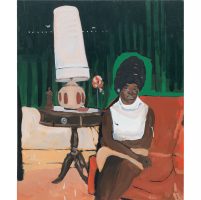

Peggy Cooper Cafritz’s Collection

After decades of art collecting, prominent activist, philanthropist, and founder of the Duke Ellington School of the Arts, Peggy Cooper Cafritz had amassed one of the most important collections of work by artists of color in the country. But in 2009, the more than 300 works that comprised this extraordinary collection were destroyed in the largest residential fire in Washington, D.C. history. The pioneering collection included art by Kara Walker, Kerry James Marshall, Mickalene Thomas, Yinka Shonibare, Nick Cave, Kehinde Wiley, Barkley L. Hendricks, Lorna Simpson, and Carrie Mae Weems, among many others.

(from left to right): Toyin Ojih Odutola, Dotun (Don’t Fret), 2011; Mickalene Thomas, Kalena, 2009; Titus Kaphar, Lost in Shadows, 2014; Allison Janae Hamilton, The March, 2014; Lavar Munroe, Is This What You Call Paradise?, 2012.

From the book Fired Up! Ready to Go!: Finding Beauty, Demanding Equity: An African American Life in Art.

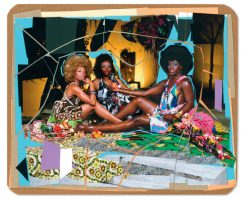

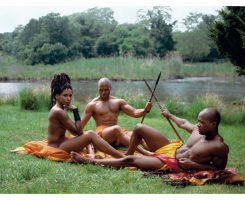

African-American Artists Take On Art History

Black artists have investigated, interrogated, invaded, entangled, annihilated, and immersed themselves in the aesthetics, symbolism, and ethos of European art for more than a century. The powerful push and pull of this relationship formed a distinct tradition for many African American artists who source the masters of art history to critique, embrace, or claim their own space. A perfect example of this important dialogue can be found in the varied interpretations of Manet’s classic “Luncheon on the Grass”, as seen here.

(from left to right): Ayana V. Jackson, Judgment of Paris, 2018; Edouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 1863; Robert Colescott, Sunday Afternoon with Joaquin Murietta, 1980; Mickalene Thomas Le Déjeuner sur L’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires, 2010; Romare Bearden, Mecklenburg Autumn: Heat Lightning Eastward, 1983; Renee Cox, Cousins at Pussy Pond, 2001.

From the book Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition.

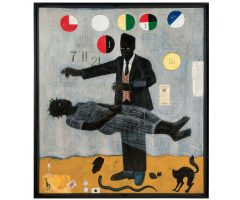

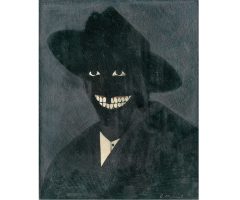

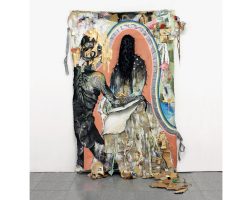

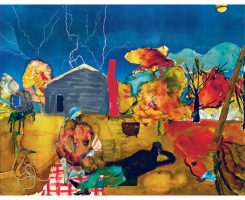

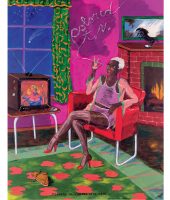

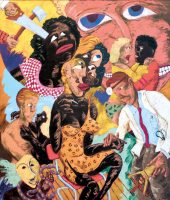

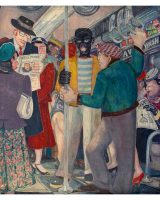

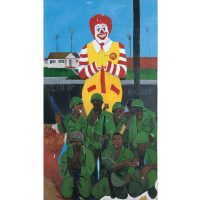

Robert Colescott

Robert Colescott (1925-2009) was a trailblazing artist, whose august career was as unique as his singular artistic style. Known for figurative satirical paintings that exposed the ugly ironies of race in America from the 1970s through the late 1990s, his work was profoundly influential to the generations of artists that have followed him, such as Kara Walker, Kehinde Wiley, and Henry Taylor, among many others. “He was a living, breathing contradiction to so many people. He looked with great reverence to art history for source material, and then at the same time he did something so very different than anything that had ever been done before, content-wise.” (Lowery Stokes Sims, co-curator of the exhibition Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott).

(from left to right): Tea for Two (The Collector), 1980; Lone Wolf in Paris, 1977; Shirley Temple Black and Bill Robinson White, 1980; Colored T.V., 1977; Grandma and the Frenchman: Identity Crisis, 1990.

From the book Art and Race Matters: The Career of Robert Colescott.

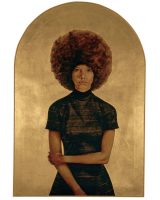

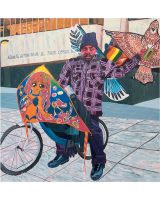

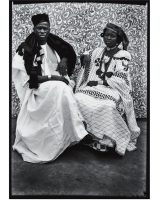

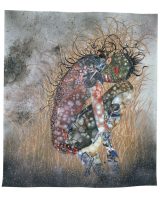

The Studio Museum in Harlem

Since its founding in 1968, the pioneering @studiomuseum in Harlem has served as a nexus for artists of African descent locally, nationally, and internationally. It holds one of the world’s most important collections of African-American art, with works by artists from Romare Bearden to Kehinde Wiley. It plays a critical role in the appreciation for the art of the African diaspora, as well as for a vital art tradition.

(from left to right): Titus Kaphar, Jerome IV, 2014; Barkley L. Hendricks, Lawdy Mama, 1969; Romare Bearden, Prelude to Farewell, 1981; Jordan Casteel, Kevin the Kiteman, 2016; Seydou Keïta, Untitled, #290, 1956–57; Wangechi Mutu, Hide ‘n’ Seek, Kill or Speak, 2004.

From the book Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem.

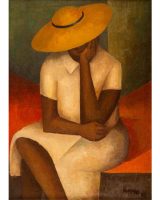

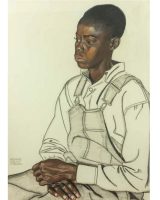

The Harlem Renaissance

Lasting from the 1910s through the 1930s, the Harlem Renaissance was a sweeping movement that saw an astonishing array of black writers, artists, and musicians gather in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood. The Great Migration at the end of the Civil War drew African American artists and scholars to the cities of the North, unleashing a myriad of talents upon the nation. The diverse artworks of this period offered the first realistic representation of what it meant to be black in America, what Langston Hughes called an “expression of our individual dark-skinned selves.”

(from left to right): Norman Lewis, Girl with Yellow Hat, 1936; Malvin Gray Johnson, Self-Portrait, 1934; Palmer Hayden, The Subway, 1941; Norman Lewis, The Dispossessed (Family), 1940; Winold Reiss, Boy of St. Helena, II, 1927.

From the book I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance at 100.

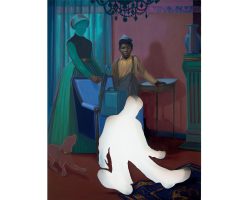

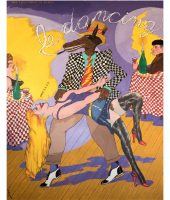

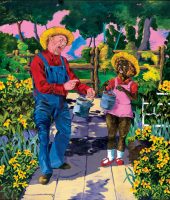

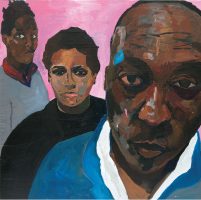

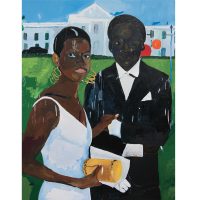

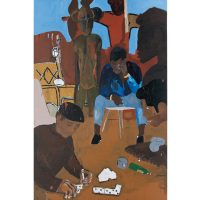

Henry Taylor

Henry Taylor’s portraits and street scenes form a personal and political portrait of society today. Taylor spent a decade working as a nurse in a California state mental hospital, an experience that informs the artist’s empathetic eye and allows him to imagine his figures with authenticity and grace—not better than they are, or more glamorous—but part of a big, complicated world. Flat, brushy flows of color cast figures that often float in surreal landscapes, while simultaneously pointing to the social and political issues affecting African Americans today.

(from left to right): i’m yours, 2015; Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas, 2017; Not Alone, 2013; Untitled, 2012–13; Cora’s, 2016; “Watch your back”, 2013; Anthony Swan, 2016.

From the book Henry Taylor.